Ancestral Stitches Palestinian Tatreez

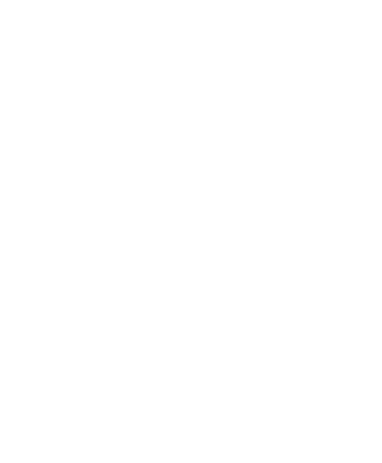

Palestine’s soil and rivers hold more than water – they carry the memory of an Indigenous, multicultural, and religiously pluralistic people who have called the land home for centuries. At the turn of the 20th century, this land was inhabited by Muslims, Jews, Christians, Druze, Baha’i, Hindus, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians, with Armenians and other ethnic minorities woven into the social fabric. Life centered around over 800 villages where fellahin, “people of the land”, cultivated an agricultural legacy.

Each village was a mosaic of homes, orchards, worship spaces, markets, and burial grounds, places that tied Palestinians to their land and to one another in familial ways.

The Thobe as Biography Palestinian Tatreez

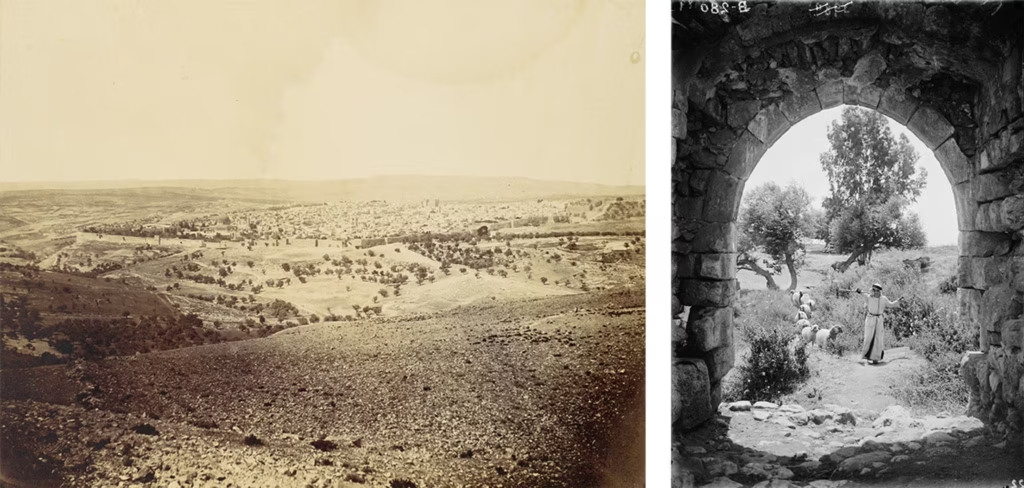

Among the most intimate records of Palestinian life is the thobe, an embroidered dress worn by women. Through tatreez, Palestinian women stitched memories into their clothing, each pattern a visual language, each thobe a biography.

These dresses bore symbols specific to each region, tribe, and social status. Wedding thobes, mourning garments, and everyday wear each told a different story. In absence of written archives, these garments became the visual diaries of Palestinian women, tangible threads of intangible heritage.

Orientalism and the Misrepresentation of Palestine Palestinian Tatreez

Despite the deep meaning behind these garments, Western museums often misrepresent them. When tourists began flocking to the Holy Land post-1892 (following the Yaffa–Jerusalem railway), Palestinian thobes were collected as biblical relics rather than living garments. Vogue even advertised “Holy Land tours,” fueling what scholars now call “Biblification” – an Orientalist practice where Indigenous Palestinians were erased in favor of mythic pasts.

As a result, dresses entered institutions like The Met without maker names, histories, or acknowledgment of their true cultural roots.

Palestine carries in its soil and rivers the collective memory of a people who have cultivated and cared for the land for centuries.

The Material Speaks Palestinian Tatreez

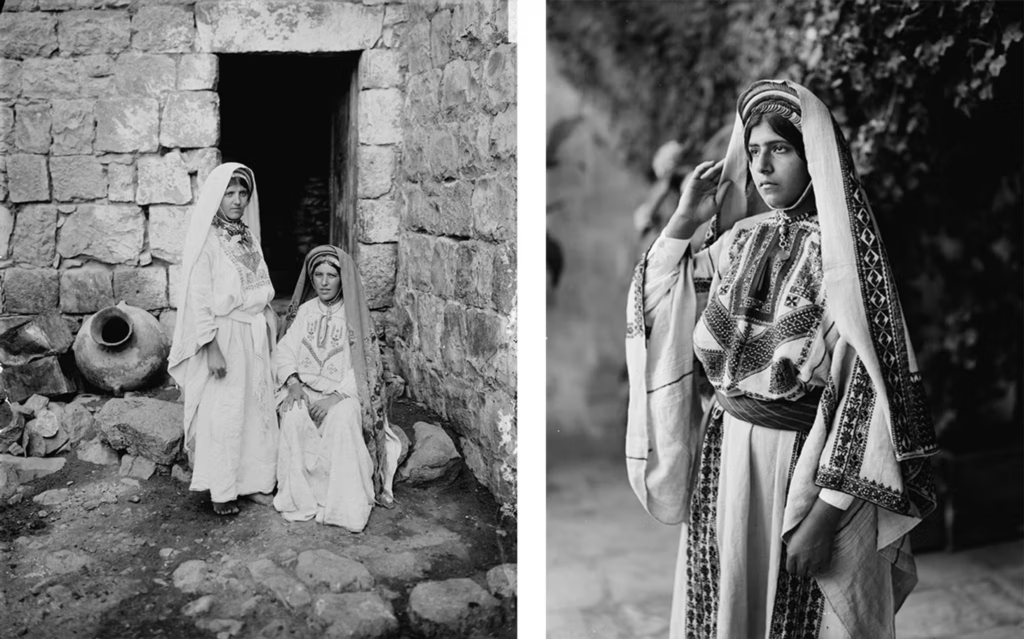

Palestinian thobes are not just beautiful, they are physically worn histories. Discoloration where a belt once sat. Knee imprints. Fraying hems. These intimate traces tell us how a woman moved through the world.

Take the Ramallah everyday dress, mid-19th century: likely sewn by a 10–12-year-old girl and her mother. The chest panel is naive, the stitching loose. Glass beads, uncommon for this region, were added by the girl; protective blue beads in the skirt were likely her mother’s addition. The dress speaks of mentorship, love, playfulness.

Tatreez was passed down orally. Patterns such as the Tree of Life (saru) or Cypress vary by village but carry shared meanings.

During the 19th century, geometric patterns dominated. By 1900, floral and zoomorphic motifs (like peacocks or winged lions) appeared, echoing European influences through missionary schools. Thread colors shifted from natural dyes (rusts, greens) to synthetic burgundies and reds.

Each stitch is an act of remembrance, resistance, and return.

Al-Khalil: Heart of Cultural Heritage Palestinian Tatreez

South of Bethlehem, al-Khalil (Hebron) is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Palestine. Here, glassmakers used Dead Sea sand to craft colorful beads. Women integrated these beads, usually reserved for jewelry, into their thobes, creating rare examples of hybrid adornment.

Heavily embroidered overcoats known as jellaya were typical. The “Tent of Pasha” pattern was specific to this region, stitched in vibrant silks to honor the local landscape, palm trees, stars, rosettes.

Each al-Khalil outfit was complete with a ghudfeh (scarf) and coin-laden taqsira (jacket). Headdresses featured real currencies from across empires, Ottoman, British, Roman, symbolising the woman’s status and protection from evil.

Some coins were functional. Others, like Maria Theresa dollars, were worn for prestige. Each headdress, like each thobe, was a portal to the wearer’s world.

The Thobe as Witness: Palestinian Embroidery, Displacement, and Resistance

Tatreez is more than adornment. It is memory. Resistance. Archive. For generations, Palestinian women stitched their lives, identities, and ties to the land into the thobe, a traditional dress. Once part of daily life, these garments now hang in museums, private collections, and refugee homes around the world, silent witnesses to a fractured homeland.

Displacement and Transformation: Al-Nakba and Beyond

The 1948 Nakba (“catastrophe”) saw over 750,000 Palestinians displaced and 418 villages emptied during Israel’s creation. Families fled with only what they could carry, often leaving behind heirlooms like thobes, some lost, looted, or absorbed into museums without provenance.

Displacement transformed tatreez from a hyperlocal, village-specific craft into a diasporic visual language. Women in refugee camps across Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and within Palestine adapted their motifs, blending styles as traditions uprooted and reformed.

Material scarcity in the 1950s halted traditional thobe production. Silks, beads, and Majdal-woven fabrics became inaccessible. In Gaza, displaced weavers tried to revive textile traditions using salvaged looms, many of which have since been destroyed, their fate unknown.

The headdresses are inherited generationally, with each wearer having the option to add a coin, bead, amulet, or medallion.

The Six-Branch Thobe: A National Symbol Emerges

Amid loss, a new symbol rose: the six-branch thobe. Once an old regional style, it reemerged post-1948 as a national dress. The aruq, six vertical panels, shifted from village identifiers to emblems of collective identity.

Refugee women adapted the design to scarcity: simplified silhouettes, narrow sleeves, thinner embroidery. As conditions improved, they thickened the panels, stitching resilience into every thread.

The Intifada Thobe: Threads of Defiance

During the First Intifada (1987–1993), tatreez took on overt political weight. The Intifada thobe, reportedly designed by Suha Arafat and produced by ANAT Workshop in Damascus, fused traditional design with national symbolism: Palestinian flag colors, resistance motifs, slogans.

With flags banned, women embroidered protest into their clothing. Under curfew and occupation, the thobe became a medium of intergenerational resistance, needlework as defiance, and a legacy passed from mother to daughter.

Embroidery as Archive Palestinian Tatreez

Before 1948, land defined identity. Each village’s tatreez carried distinct patterns rooted in geography. Dispossession severed this bond. Exiles likened their displacement to death, burial, erasure. Today, elders call visits to their lost villages hajj, a pilgrimage.

So what happens to the thobe, this living archive, when it is separated from its land and maker? It remains, an object of memory, a record of survival, and a quiet, persistent claim to belonging.

Palestinian Tatreez Palestinian Tatreez Palestinian Tatreez v v Palestinian Tatreez Palestinian Tatreez Palestinian Tatreez v Palestinian Tatreez